What is a tide gauge?

Be it analog, acoustic, or microwave, a tide gauge measures changes in sea level relative to a datum (a height reference).

The rise and fall of the tides play an important role in the natural world and can have a marked effect on maritime-related activities. The image aboves shows the NOAA San Francisco Tide Station, in operation for more than 150 years.

A tide gauge, which is one component of a modern water level monitoring station, is fitted with sensors that continuously record the height of the surrounding water level. This data is critical for many coastal activities, including safe navigation, sound engineering, and habitat restoration and preservation.

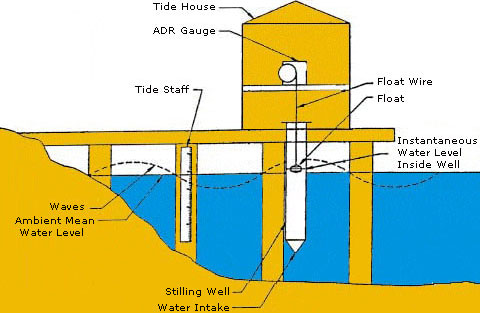

Before computers were used to record water levels (especially tides), special "tide houses" sheltered permanent tide gauges. Housed inside was the instrumentation—including a well and a mechanical pen-and-ink (analog) recorder—while attached outside was a tide or tidal staff. Essentially a giant measuring stick, the tide staff allowed scientists to manually observe tidal levels and then compare them to readings taken every six minutes by the recorder. Tide houses and the data they recorded required monthly maintenance, when scientists would collect the data tapes and mail them to headquarters for manual processing.

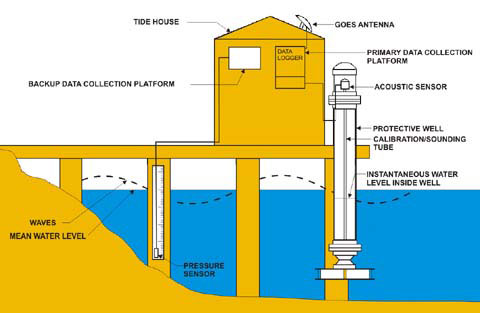

The New

While similar in design to older tide houses, newer tide station enclosures are designed to protect sensitive electronics, transmitting equipment, and backup power and data storage devices. The older stilling well has been replaced with an acoustic sounding tube and the tidal staff with a pressure sensor. The new field equipment is designed to operate with the highest level of accuracy with a minimum of maintenance, transmitting data directly back to NOAA headquarters for analysis and distribution.

The Old

Before computers, special "tide houses" were constructed to shelter permanent water level recorders, protecting them from harsh environmental conditions. In this diagram, we can see how the analog data recorder is situated inside the house with the float, and the stilling well located directly beneath it. Attached to one of the piers' pilings is a tidal staff. This device would allow scientists to manually observe the tidal level and then compare it to the readings taken by the analog recorder.

The computer age led to tide gauges that use microprocessor-based technologies to collect sea-level data. While older tide-measuring stations used mechanical floats and recorders, modern monitoring stations use advanced acoustics and electronics. Today's recorders send an audio signal down a half-inch-wide "sounding tube" and measure the time it takes for the reflected signal to travel back from the water's surface. Data is still collected every six minutes, but while the old recording stations used mechanical timers to tell them when to take a reading, a Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES) controls the timing on today's stations.

In addition to measuring tidal heights more accurately, modern water level stations are capable of measuring 11 other oceanographic and meteorological parameters, including wind speed and direction, air and water temperature, and barometric pressure. NOAA uses this information for many purposes, among them to ensure safe navigation, record and predict sea-level trends and other oceanographic conditions via nowcasts and forecasts, and publish annual tide predictions.

Search Our Facts

Get Social

More Information

The Next Generation

A revolutionary step forward in how NOAA measures water levels is with microwave radar water level sensors. They represent a significant technological improvement over acoustic sensors, and the Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services is in the process of transitioning most of its stations over to this technology. At present, they are the primary sensors at about 40 of NOAA's 210 National Water Level Observation Network (NWLON) permanent stations and its 29 Physical Oceanographic Real Time Systems (PORTS®), which are located throughout the U.S. and its territories.

Last updated: 06/16/24

Author: NOAA

How to cite this article