Rip Currents

Currents Tutorial

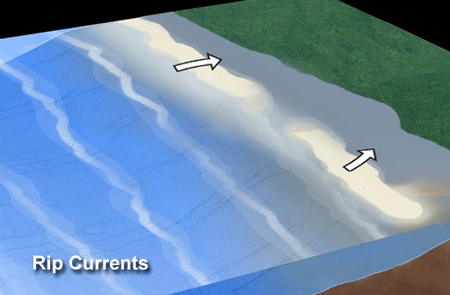

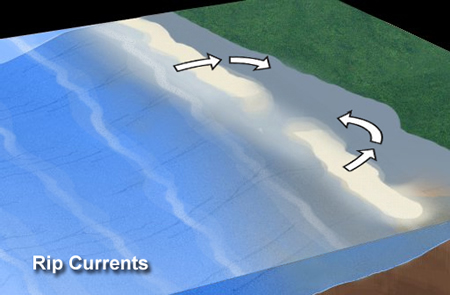

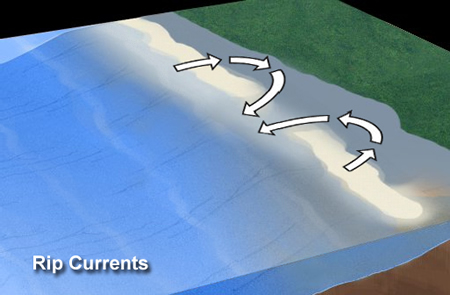

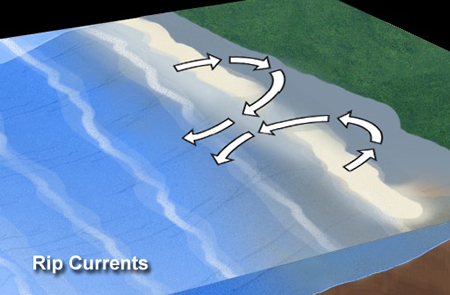

As longshore currents move on and off the beach, “rip currents” may form around low spots or breaks in sandbars, and also near structures such as jetties and piers. A rip current, sometimes incorrectly called a rip tide, is a localized current that flows away from the shoreline toward the ocean, perpendicular or at an acute angle to the shoreline. It usually breaks up not far from shore and is generally not more than 25 meters (80 feet) wide.

Rip currents typically reach speeds of 1 to 2 feet per second. However, some rip currents have been measured at 8 feet per second—faster than any Olympic swimmer ever recorded (NOAA, 2005b). If wave activity is slight, several low rip currents can form, in various sizes and velocities. But in heavier wave action, fewer, more concentrated rip currents can form.

Because rip currents move perpendicular to shore and can be very strong, beach swimmers need to be careful. A person caught in a rip can be swept away from shore very quickly. The best way to escape a rip current is by swimming parallel to the shore instead of towards it, since most rip currents are less than 80 feet wide. A swimmer can also let the current carry him or her out to sea until the force weakens, because rip currents stay close to shore and usually dissipate just beyond the line of breaking waves. Occasionally, however, a rip current can push someone hundreds of yards offshore. The most important thing to remember if you are ever caught in a rip current is not to panic. Continue to breathe, try to keep your head above water, and don’t exhaust yourself fighting against the force of the current.

Currents Lessons

- Welcome

- Tidal Currents 1

- Tidal Currents 2

- Waves

- Longshore Currents

- Rip Currents

- Upwelling

- The Coriolis Effect

- Surface Ocean Currents

- Boundary Currents

- The Ekman Spiral

- Thermohaline Circulation

- The Global Conveyor Belt

- Effects of Climate Change

- Age of Exploration

- What is a "knot"?

- Shallow Water Drifter

- Deep Ocean Drifter

- Current Profiler

- Shore-based Current Meters

- How Currents Affect Our Lives?

- References

- Roadmap to Resources

- Subject Review