Coral Bleaching

NOAA Ocean Podcast: Episode 71

When temperatures rise, coral bleaching can occur. In this episode, we explore what happens during bleaching events, how corals are affected, and how we can help protect these important ecosystems. We’re joined by coral expert Dana Wusinich-Mendez, Atlantic and Caribbean team lead, and Florida management liaison for NOAA's Coral Reef Conservation Program.

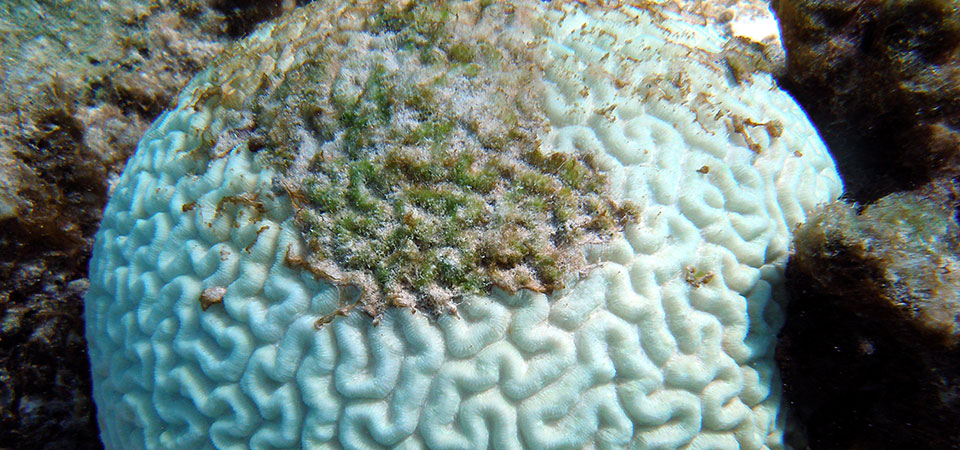

This image shows a bleached brain coral. When bleaching occurs, a microscopic algae that lives inside of corals either dies or is expelled by the coral. The algae is what gives corals their colors.

Listen here:

Or listen in your favorite podcast player:

Transcript

HOST: This is the NOAA Ocean Podcast, I’m Marissa Anderson. When corals experience stress, coral bleaching can occur. These bleaching events can have widespread impacts beyond the corals and the ecosystems they are found in. In this episode, we explore what bleaching is, some of the factors that cause it, and what we can do to prevent it. We’re joined today by Dana Wusinich-Mendez, Atlantic and Caribbean Team Lead and Florida Management Liaison for NOAA's Coral Reef Conservation Program. Dana starts us off with a basic definition of coral bleaching.

Dana Wusinich-Mendez, Atlantic and Caribbean team lead, and Florida management liaison for NOAA's Coral Reef Conservation Program.

WUSINICH-MENDEZ: So coral bleaching occurs when a microscopic algae that we call zooxanthellae that lives inside of corals, either dies or is expelled - gets kicked out by the coral. Zooxanthellae are what give corals their vibrant colors. Corals themselves consist of a coral animal or a polyp that’s surrounded by a white skeleton that those polyps build. So when corals get stressed out, if something is going on in the environment, say increased temperatures, the algae inside of them can either die or get expelled by the coral. And so what is left is that transparent polyp and that white skeleton making the coral look either white or bleached. So stony corals in tropical marine ecosystems are reliant on a relationship with that algae, that zooxanthellae that we talked about earlier. Corals provide habitat or a place to live for the zooxanthellae and the zooxanthellae are an important source of energy for corals. In fact, as much as 90 percent of the organic material produced by those algae conducting photosynthesis is actually transferred to the coral animal itself. And this relationship between corals and zooxanthellae is really the driving force behind the growth and the productivity of coral reefs. Corals have very specific temperature requirements and they typically don’t withstand temperatures that are cooler than about 65 degrees fahrenheit nor warmer than 90 degrees fahrenheit. So when water temperatures get too warm or too cool, corals become stressed. And when corals become stressed, they expel that zooxanthellae. So there's definitely a relationship to climate change because climate change is not only making it hotter on the land, it's also causing increased ocean temperatures and periods of prolonged heat stress for marine ecosystems like coral reefs. And these changes are especially significant in the shallow tropical waters where many corals are found.

HOST: It sounds like the bleaching is pretty detrimental to corals. What are the negative impacts?

WUSINICH-MENDEZ: First thing, it's important to realize that when a coral first bleaches, it's not actually dead yet. So corals can survive a bleaching event. If it's not too severe and the temperatures don’t go too high, and if the heat stress doesn’t last too long, corals, the zooxanthellae, can reinhabit corals and then corals can survive that event. If the event is severe and the water is too warm or too cold, or one of those things for too long, then the coral polyps themselves will die. Dead corals change the composition of a reef, and can result in the loss of important species and important habitat for so much of the marine life that depends on them.

HOST: So if corals are impacted by a bleaching event, is there a recovery period that they need to go through?

WUSINICH-MENDEZ: There are definitely some long-term effects even when corals recover. They may look the same to our eyes, but once they survive a bleaching event like that, their overall health has been compromised and so for example, we often see coral disease outbreaks following coral bleaching events because those corals have become more susceptible to disease. Those corals that have recovered also have less energy available to build those skeletons that we talked about earlier and to reproduce. You know, the same thing happens to us when we get sick, when we get a cold or a flu, even after we recover from that, again, we’re still not completely back to ourselves and healthy for some time. And it takes awhile for our energy levels to return to normal, and you can say the same thing for corals.

HOST: Aside from the impacts to the corals and the zooxanthellae, are there impacts beyond that, say to the organisms that live around the coral and in the coral reef ecosystems impacted by the bleaching?

WUSINICH-MENDEZ: You know, corals build reefs, and reefs create habitats, and that habitat creates protection for many marine organisms. Corals are themselves, are food sources for other marine marine animals or they provide habitat for food sources for other marine animals. So when corals die and coral reefs are degraded, they affect the food web, they affect the productivity of our oceans and more. And they affect us as humans, we rely on coral reefs. We rely on reefs for food - lobster, snapper, grouper, many of the fish we like to eat. We rely on coral reefs to provide shoreline protection for coastal communities. They act as natural barriers to wave action that gets generated by storms, so those corals can reduce the impact of those storms on coastal communities. And we rely on coral reefs as a source of income in many places, and for our cultural and social identities, so if coral reefs are impacted, so are we.

HOST: I’m sure many people may not realize the connection we have as humans to the coral reefs. Can you describe to us the bleaching events that took place this year in the summer of 2023?

WUSINICH-MENDEZ: In the middle of July 2023, we had some of the hottest water temperatures ever documented in the region, going back to satellite records from 1985. It was a heatwave event. And our corals in the Florida keys, not only began bleaching, but actually the temperatures got so high, that some of the corals just died immediately from the extreme temperatures. So it not only affected the Florida keys, but it’s ongoing throughout the wider Caribbean region. This heatwave event continues to expand and might eventually become a global coral bleaching event. At least thirty five countries and territories in five different oceans and seas have already reported bleaching on their reefs. And currently in the Caribbean we are experiencing a basin-wide mass bleaching event.

HOST: Where were these events so significant?

WUSINICH-MENDEZ: The heatwave in Florida and around the Caribbean occurred earlier than ever before. It lasted longer than previous heatwaves and bleaching events, and it really shattered previous records in terms of temperature levels. The heat stress is still ongoing in the Caribbean and we are not expecting it to fully dissipate until December. But the extremely high temperatures and the fact that it started so early, leading to such a prolonged period of elevated temperatures really made life difficult for our corals and our coral reef ecosystems.

HOST: What can be done to help mitigate the effects of bleaching on the reefs?

WUSINICH-MENDEZ: We are working to develop interventions that can be applied to reduce those impacts of heat stress. For example, people are trying things like shading of corals, cooling corals, removing other stressors that affect coral health so that they are in the best shape possible to withstand those heat stress events. Doing things like feeding corals just to try and make life easier for them, as easy as possible so that they can survive these events. So we need to continue to test and explore new interventions that can be taken to help corals survive these events. Another thing that can be done, or is being done is resilience based restoration. So that means, using new innovations in coral science to understand why some corals survive stress events like bleaching events or coral disease outbreaks, and to apply that knowledge to than produce corals that have greater heat tolerance and resilience to these threats, and to use those more resilient corals to restore our coral reefs. We really need to provide added protection to areas where corals survive these stress events. These are important places and they are the future of coral reef ecosystems so we need to identify reef areas that survive stress events such as bleaching events and establish additional protections possibly through the establishment of marine protected areas or the implementation of measures to improve water quality of these areas.

HOST: You had previously talked about resilience based restoration. Can you provide an example of that?

WUSINICH-MENDEZ: Restoration is an important tool in the conservation toolbox that we’re using to try and save existing coral reefs. There are many different restoration approaches and techniques. One way of doing restoration is to remove healthy corals or portions of healthy corals from the ocean to protect them from stressful events like disease outbreaks or bleaching events, to than use those coral fragments to grow corals within nurseries or to produce and facilitate reproduction in corals in nurseries on land or in the ocean. New corals can then be planted back out onto coral reefs that have been impacted by disturbance like a major heat stress event or a hurricane or reefs that are damaged by a boat. Restoring corals in the wild is most successful when we are able to identify and use resilient corals or types of corals that are better able to withstand impacts to their environment like rising ocean temperatures.

HOST: You had mentioned earlier that one of the mitigation techniques was coral shading. Can you tell us a little more about what that is?

WUSINICH-MENDEZ: It actually is what it sounds like, creating shade over coral reef areas. There are scientists both within NOAA and NOAA’s partners who do coral reef conservation who are actually constructing shade structures. So it could be a piece of tarp that somehow fastened above a coral reef area or a coral nursery to reduce that UV radiation, to reduce the amount of sunlight that is reaching those corals, to keep things cooler just like we sit under an umbrella at the beach to stay cooler. The idea is that providing the shade to corals may reduce their heat stress.

HOST: Is there anything that the public can do to either help prevent these events, or that the public can assist with response efforts when these events take place.

WUSINICH-MENDEZ: Yes, there are so many things that we can all do - broadly as well as getting directly involved with coral reef conservation or when an event like this is taking place. We can join Citizen Science programs and get involved. Here in Florida, we actually have two Citizen Science programs. We have the Sea Fan program in southeast Florida and in the Florida Keys, we have the Bleach Watch Program. Where normal people, just like you and me, can get involved and collect information on bleaching corals for reef managers and scientists to help them make management decisions and give them the best information possible. We can minimize additional stress to coral reefs by wearing sun protective clothing instead of using sunscreens, avoiding anchoring near live coral habitat to avoid those unintended impacts to corals, keeping our hands, feet and fins away from corals, avoiding the use of things that could pollute the marine environment such as herbicides and fertilizers during rainy seasons as those things get carried to the reef as polluted runoff. And then because of that connection between coral bleaching and climate change, we can work to reduce our carbon footprint. We can drive and fly less, we eat less meat, buy local, save energy, use renewable energy, or plant a tree. And we should support policies and measures to reduce the emissions of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere to mitigate climate change. And then most importantly, we can teach people about coral reefs and how important they are.

HOST: That's a great point you made about reducing your carbon footprint, so no matter where you live - either in a coastal community or a landlocked state, we can all do our part to help protect the corals. This has been the NOAA Ocean Podcast. Thanks for listening and check out our show notes to learn more about coral reefs. Be sure to catch all our episodes in your podcast player of choice.

From corals to coastal science, connect with ocean experts to explore questions about the ocean environment.

Social