The Exxon Valdez, 25 Years Later

Making Waves: Episode 122

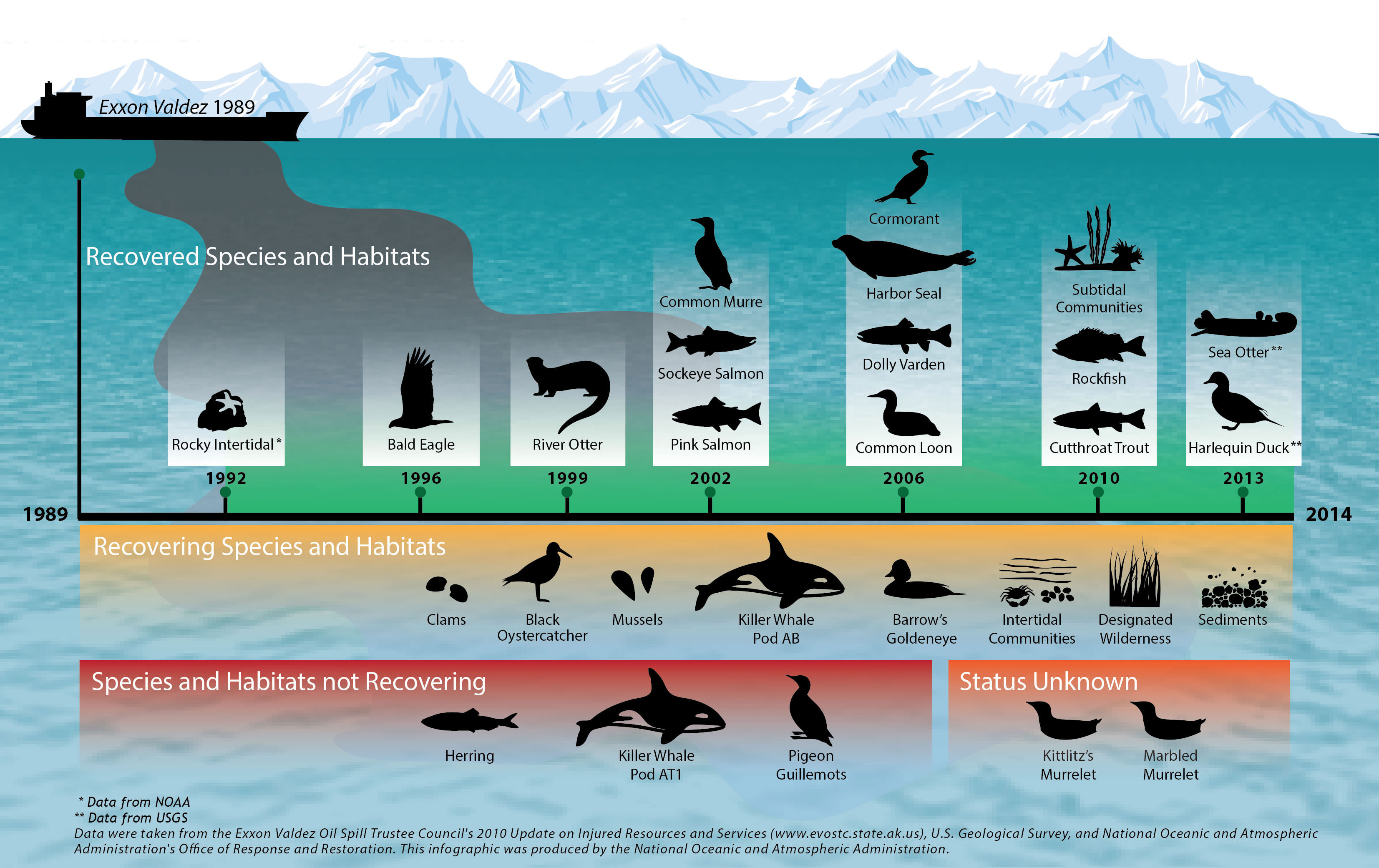

Recovery Timeline

The tanker Exxon Valdez spilled almost 11 million gallons of oil into Alaska's Prince William Sound on March 24, 1989, injuring 28 types of animals, plants, and marine habitats. How long has it taken them to recover from this spill? Twenty-five years later, which ones have not recovered? Here is a timeline showing when natural resources were declared officially "recovered," through actual recovery could have occurred earlier than this official designation from the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council. Click/tap on the map for a larger view | Download this graphic

Listen:

In this podcast, we talk with NOAA marine biologist Gary Shigenaka to find out how marine life is faring in Prince William Sound today. We also look at lessons we might learn from this environmental disaster in light of growing oil exploration and shipping traffic in the Arctic.

Transcript

[SHIP RADIO] "Yeah, this is Valdez. We've ... should be on your radar there. We've fetched up, hard aground, north of Goose Island off Bligh Reef and ... evidently ... leaking some oil ... "

[NARRATOR] That radio call was made on March 24th, 1989. An oil tanker had struck Bligh Reef in Alaska's Prince William Sound. It was the beginning of one of the biggest environmental disasters in U.S. history. This is Making Waves from NOAA's National Ocean Service. I'm Troy Kitch. In today's show, the Exxon Valdez oil spill—twenty-five years later. After the Exxon Valdez spilled nearly 11 million gallons of crude oil into the ocean, a team of NOAA scientists arrived on-scene to provide scientific support during the long clean-up. Biologist Gary Shigenaka was a member of that team. The Exxon Valdez was his first introduction to working on a big oil spill for NOAA.

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "It changed the course of my career and possibly even my life and it really defined the challenges of understanding environmental disturbance in a complex setting like Prince William Sound."

[NARRATOR] That's Gary, and he's with us today by phone from his Seattle office where he works as a biologist in NOAA's Response and Restoration office. He said that part of what made this spill unique was not only its size, but that it happened in such a remote place. There just weren't any response assets that could quickly be called up to go clean up the oil:

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "... like vessels, airplanes, and people and specialized pieces of gear like containment boom. Prior to that other recent spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the Deepwater Horizon, it was the largest spill to occur in U.S. waters and it was a benchmark in a lot of ways. The shortcomings that were identified during the initial and longer-term response resulted in major changes to U.S. law, primarily expressed in a piece of legislation known as the Oil Pollution Act of 1990."

[NARRATOR] That law led to things like making sure we were more prepared and better trained to deal with spills, prepositioning equipment around the nation, and requiring all oil tankers in the U.S. to have double hulls -- but these changes only tell part of the story. The kind of change we're going to talk about for the rest of the show doesn't involve improvements in ship hull design, new laws, or better training ... it involves nature. And how scientists try to figure out what's going on in nature. Twenty-five years later ... how is this remote region of Alaska faring? That's a question that we'll see is not so easy to answer. Remember when Gary said that this spill defined the challenges of understanding environmental disturbance in a complex setting? What exactly does that mean? Well, he said Prince William Sound is a very complex ecosystem, a place with gravely intertidal areas, glaciers, and exotic wildlife like whales, salmon, and sea otters. And, above all, it's a region where the environment is constantly in flux. This area changes rapidly from year to year.

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "Our monitoring program after the spill really showed how variable the Prince William Sound marine environment is even without a disturbance like the spill. So this is looking at what we call the unoiled, what we call the 'control sites,' and this inherent variability has translated into big challenges for tracking the signal of the spill, especially after the first year or two after it begins to fade a little bit, then it's get harder to separate the signal of the spill from the inherent background variability that is characteristic for Prince William Sound. Basically, if things are changing a lot at the sites you're monitoring and it isn't linked to the oil spill, you know, how do you define when things are back to 'normal,' in quotes I guess that would be."

[NARRATOR] Adding to this 'inherent variability,' there was something else to consider.

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "And the other thing that made it unique at the time of the spill was the fact that it really was still recovering from another major disturbance that happened exactly 25 years before the Exxon Valdez and that was the Great Alaskan earthquake, which was one of the largest that's been recorded to date. And we can really focus in on Prince William Sound because Prince William Sound was one of the most impacted areas in Alaska. There were places that were uplifted as much as 30 feet during that particular earthquake. So you can imagine the shorelines changed really radically. So then we would have a human event superimposed on a large-scale natural event. So it's a complex kind of picture."

[NARRATOR] So given all of these variables, can we really say anything about how fish, animals, and plants are recovering from the spill? Gary said in some cases, yes. But it often depends on knowing what conditions were like before the spill happened.

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "Whenever we have a spill or when we're trying to assess the impact of any action or disturbance on an environment in question, we always ask, 'well, what were things like beforehand.' And for oil spills, we rarely know. In the case of the Exxon Valdez, there was one exception, and it's proved to be important."

[NARRATOR] The exception was a monitoring program of orcas that had been ongoing in the Sound for at least five years before the spill.

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "That pre-spill information showed that something in 1989 drastically reduced the numbers of orcas in two groups that frequents Prince William Sound and that's something that's mostly unheard of in generally stable populations of large marine mammals. And then the continuing monitoring after the spill has shown a very disturbing recovery pattern. One not so disturbing: one group of orca whales in Prince William Sound is slowly recovering, but the other group of orcas is declining towards extinction. So that kind of demonstrates what the value is of pre-spill information, but again, it's very rarely available, so the next best thing that we've got for comparing oiled or cleaned site conditions to those of unoiled sites is to look at comparable sites that were not subject to the impact, in this case the oil spill."

[NARRATOR] After the spill, other long-term monitoring studies were started, some of which are still ongoing to this day. One study looked at how the gravel and rocky shorelines along the Sound recovered from some of the more aggressive clean-up methods used to remove oil. Were shorelines more damaged by the clean up than the oil alone? The answer: yes. But the flip side is that these beaches also recovered quite quickly. And this points to a reality of cleaning up oil spills: it's often about choosing between tradeoffs.

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "There was more damage, but the shoreline communities fairly quickly compensated for that additional damage and, within a year or two, they were about at the same place, and then after three or four years, most of the damage from both oil and clean up was gone. So we could say they were effectively recovered. So you put that into a clean up context and you try to determine what the tradeoffs are. Are you willing to accept that kind of a cost to get more oil out of the environment, and that's something that happens all the time in terms of in making your choices for oil spill clean up methods."

[NARRATOR] And then there are still things that science can't yet explain. I asked Gary what's most surprising today about this spill after so many years.

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "There's still pockets of oil in some places in Prince William Sound and along the Alaskan Peninsula and it's still relatively fresh. I don't think anyone really expected that after 25 years and we don't fully understand why. I think that's something that'll be important to try to figure out for the future."

[NARRATOR] Unexpected pockets of relatively fresh oil, gravel beaches that returned pretty much to normal after four or five years, animal populations that have recovered or are still trying to recover today...how do scientists deal with so much often conflicting data? How can we know if changes or recovery times are due to the oil spill or if there are other factors at play? How do we know when an area is 'recovered?' This all points back at what Gary says is the main take-away lesson after 25 years of studying the aftermath of this spill: the natural environment in Alaska and in the Arctic are rapidly changing. If we don't understand that background change, than it's really hard to say if an area has recovered or not after a big oil spill.

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "I think we need to really keep in mind that maybe our prior notions of recovery as returning to some pre-spill or absolute control condition may be outmoded. We need to really overlay that with the dynamic changes that are occurring for whatever reason and adjust our assessments and definitions accordingly. I don't have the answers for the best way to do that. We've gotten some ideas from the work that we've done, but I think that as those changes begin to accelerate and become much more marked, then it's going to be harder to do."

[NARRATOR] So given what we've heard so far, 25 years later, is Prince William Sound generally considered recovered from the Exxon Valdez oil spill?

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "No. There's a pretty robust research program that's been going on in Prince William Sound -- not just ours -- but a whole series of research and monitoring activities and mostly under the auspices of the Exxon Valdez oil spill trustee council."

[NARRATOR] He said that this group has been looking at a fixed set of resources for nearly the entire time that has passed since the spill.

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "And slowly but surely, there list of impacted resources has been switching from one column, impacted, to another column, recovered. And most recently, they've moved a couple of persistent unrecovered resources -- and that would be sea otters and harlequin ducks—from the 'not recovered' column to the 'recovered' column. So that's good news but we've still got a handful of resources that remain in the 'not recovered' column, including the orcas I mentioned. The short answer to the question, I think, is because not everything has moved over to the recovered column, then you can't really say that Prince William Sound has recovered.

[NARRATOR] But, he added, Prince William Sound has made a lot of progress over the past two and a half decades.

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "It's in some ways encouraging to see that the environment can rebound from something like a major oil spill, but it is still a little distressing that we can't just say 25 years after the fact that things have recovered completely."

[NARRATOR] Gary attributed most of that progress in environmental restoration not to human efforts, but to the resiliency of nature.

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "Nature has pretty much on its own—I mean we did some good with the clean up but the estimates of how much oil that our clean up efforts removed from the environment versus the amount of oil that was naturally degraded or removed from the environment, it's pretty discouraging in terms of the scale of the efforts that we posed during the spill. It comes out somewhere between 10-15 percent of the total oil spilled was recovered by our clean up efforts. So the natural environment pretty much does the job on its own. We can help a little bit, and I think we can make a big difference for highly sensitive areas, but for the most part we're just a footnote to oil spill clean up from the environment overall."

[NARRATOR] So what we know is that things have improved over time since the spill in Prince William Sound, but it's hard to quantify because the environment is changing so quickly and in so many ways. This variability and rapid change is perhaps most profound in the Arctic. And as the Arctic continues to warm and the prospect of more human activity in this region seems inevitable -- think shipping and oil exploration—what can Exxon Valdez teach us?

[GARY SHIGENAKA] "Well I think, for us, the very concept of an oil spill in the Arctic is scary and there's a lot of reasons for that. First of all, it's obviously really a difficult environment to work in because of the weather, and then logistically, as well as culturally. So if you thought that Prince William Sound was remote, then responding to a spill in the Arctic would be almost like working on the moon. But also from an assessment perspective, the Arctic is kind of on the leading edge of some of the most rapid and radical changes that are taking place in the natural world. People who live in that area talk about the absence of long-term ice -- the old ice that used to be a part of their environment or the fact that their cellars that they use as natural refrigerators and freezers now are melting and flooding. So the Arctic communities are really bellwethers for the changes that occurring related to climate change and a lot of the other large-scale influences that are taking place because of human influences. So that's really going to affect our ability to characterize impact and recovery for the same reasons that it's difficult to do a place like Prince William Sound from the Exxon Valdez."

[NARRATOR] That was Gary Shigenaka, marine biologist with the Emergency Response Division of NOAA's Office of Response and Restoration. This is Making Waves from NOAA's National Ocean Service. Subscribe to us in and leave us some feedback about what you think of the show. We'll return in a few weeks with a new episode.

From corals to coastal science, catch the current of the ocean with our audio and video podcast, Making Waves.

Subscribe to Feed | Subscribe in iTunes