What are hydrophones?

The ocean is full of constant noise. Hydrophones pick up those sounds thousands of miles away.

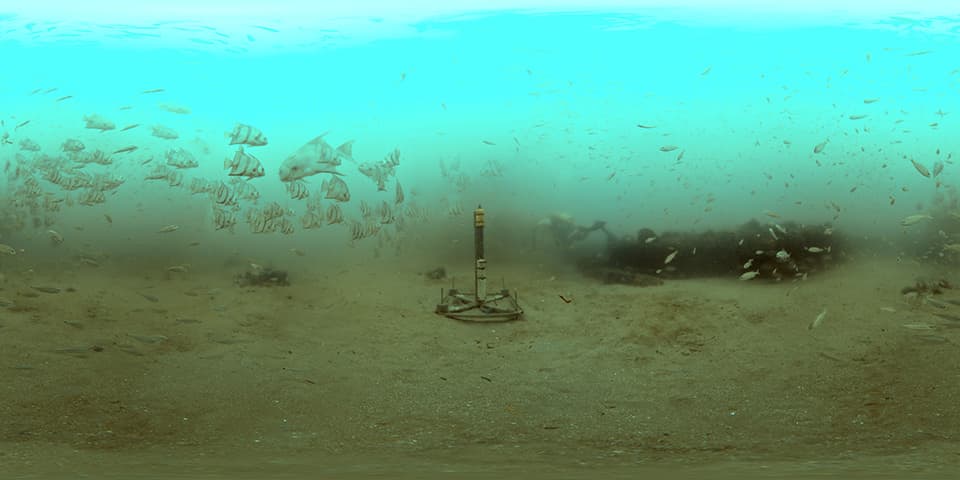

Scientists deployed five hydrophones, including the one pictured, off the eastern side of the southern tip of Greenland.

Just as microphones collect sound in the air, hydrophones detect acoustic signals underwater. Most hydrophones are based on a special property of certain ceramics that produce a small electrical current when subjected to underwater pressure changes. When submerged in the ocean, a ceramic hydrophone produces small-voltage signals over a wide range of frequencies as it is exposed to underwater sounds disseminating from any direction.

By amplifying and recording the electrical signals produced by a hydrophone, sound in the ocean can be measured with great precision. A single hydrophone records sound arriving from any direction. However, several hydrophones can be simultaneously positioned in an array, often thousands of miles apart, resulting in signals that can then be manipulated to “listen” in any direction with even greater sensitivity than a single hydrophone.

NOAA uses hydrophones and other technologies to acquire long-term data sets of the global ocean acoustics environment, to identify and assess acoustic impacts from human activities and natural processes on the marine environment, such as underwater volcanoes, earthquakes and icequakes.

Search Our Facts

Get Social

More Information

Did you know?

"You would think that the deepest part of the ocean would be one of the quietest places on Earth. Yet there is almost constant noise. The ambient sound field is dominated by the sound of earthquakes, both near and far, as well as distinct moans of baleen whales, and the clamor of a category 4 typhoon that just happened to pass overhead." Robert Dziak, NOAA research oceanographer and scientist.

Last updated:

06/16/24

Author: NOAA

How to cite this article