Coral Bleaching

December 1, 2014

Diving Deeper: Episode 58

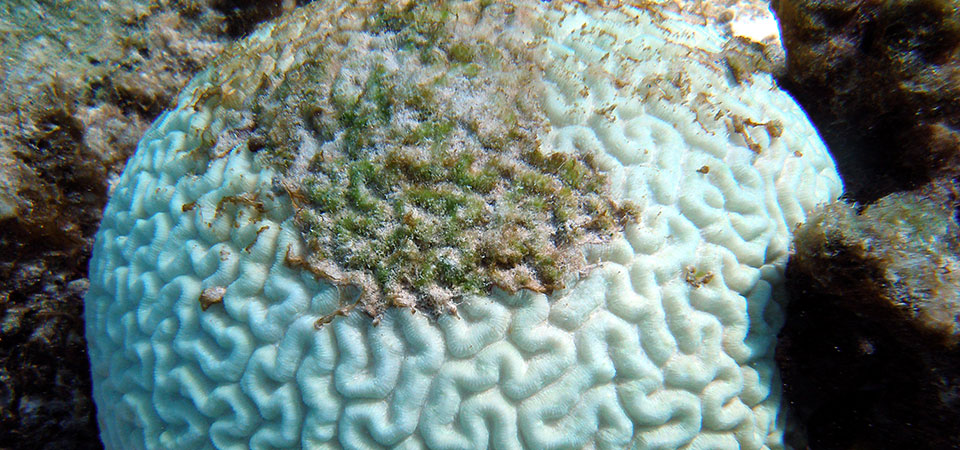

What happens when a coral bleaches?

This image shows a bleached brain coral.

Transcript

After a short break, Diving Deeper is back! Thank you for tuning in for this special dual-interview as part of our Corals Week. I'm your host, Kate Nielsen.

Today we will explore ocean acidification and coral bleaching. A special welcome today to Jennifer Koss, the Acting Director for NOAA's Coral Reef Conservation Program, and Mark Eakin, the Coordinator for NOAA's Coral Reef Watch. Hi Jennifer and Mark, thanks for joining us today!

JENNIFER KOSS: Thanks for having us. MARK EAKIN: Great to be here.

HOST: Jennifer, I asked your colleague, John Christensen this question last year on Diving Deeper when we interviewed him, so it's a good opportunity to see where we stand today. What can you tell us about the health of our coral reefs now in 2014?

JENNIFER KOSS: Well, I wish I could say that overall things were improving, but unfortunately that's just not the case. For instance, this summer we recently observed a whole bunch of bleaching events in the Pacific and the Caribbean that were unexpected. We had bleaching events in both the main eight islands as well as Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and Guam, Florida, a few places reported internationally as well; and in the Florida Keys it’s the worst bleaching incident we've seen since 1998. And then in general the local stressors that corals experience are still there and the global stressors continue to increase.

HOST: Can you expand on what you mean when you say these stressors that our corals face today?

JENNIFER KOSS: Another word for stressors would be threats. The Coral Program tends to define the threats as local and global and the local threats are kind of impacts from land-based sources of pollution as well as impacts from fishing. And the fishing in general, globally-speaking, a lot of our fisheries are either exploited to the max if not over-exploited. It's not quite the case in the United States, but if you're looking worldwide that's certainly the case. So you've got everything from gear impacts interacting with the corals as well as the effects of removing fish off of the reef and that tends to get things off kilter, so if you're removing the herbivores which keep the algae levels down on the reef, you're causing big shifts in the way that these coral ecosystems function. And then gear impacts can be everything from literally colliding with a coral reef to people who dynamite fish or cyanide fish and it's kind of more adding insult to injury there; and then our other big local impact would be land-based sources of pollution and that can be anything from sediment coming off of the land to nutrients and toxins coming off the land and then the plastics that seem to be increasing and becoming more globally distributed. And then global impacts, which Mark will talk far more about, would be all of the impacts from climate change so warming sea water temperatures, sea level rise, ocean acidification.

HOST: So, unfortunately it is quite the host of threats that our corals are seeing. I think for today's episode I'd like to look a little bit more at this effect of warming waters on our corals and I'll open that up to both of you to chime in.

JENNIFER KOSS: So I'll kick it off and then hand it over to Mark. In general, when corals experience a thermal stress, the algae that exist within the coral tissues, they're symbiotic zooxanthellae, the corals will expel them. So the color that you see on a coral is actually due to the algae that's in the tissues so when the algae is expelled the corals themselves are translucent so you get this bleached effect so that's the overall net impact of too quickly and too much warm water in a coral ecosystem.

MARK EAKIN: You know when the water warms up, what happens is it's actually good for the algae in one way in that it makes all of their photosynthetic apparatus run really great, but the problem is they run too fast; and as they run too fast they're not able to repair themselves and the lack of repair causes the algae to start releasing compounds that are toxic to the corals. The coral sees this as, "whew, we've gotta get rid of you because if we don't, we're both going," and they will actually eject the algae out from their tissues. They move them into the guts, spit them out—it's a literal gut-wrenching experience when they do this. They're breaking up pieces of tissue to get rid of this, to slough it off.

What happens is the coral is actually clear, the tissue of the coral is actually clear and that maximizes the light that can get through and get to the zooxanthellae, these symbiotic algae. Well, when the corals kick all of these algae out, it allows the light to get through to the white skeleton underneath. And you're looking at it, you're seeing white skeleton. It looks like it's been bleached, but you've actually got live tissue over the top, it's just very difficult to see unless you look really close.

Now if the event is mild enough and doesn't last too long, the corals are able to recover their zooxanthellae, go back to normal. Although they have been stressed. They have been damaged. It does makes them more susceptible to other types of disease, just like you or I are more susceptible to the common cold if our bodies are stressed—if we're not getting enough sleep, not enough rest, a lot of stress at work, whatever. Now if the event is really severe, then the problem is when these algae are gone, the corals have lost most of their food source, so they're actually starving at this point. So the longer this lasts, the less other food that's available to them, the quicker the corals are going to die.

Now that's what happens at an individual level, but if you think about the entire reef what can happen is a reef that's bleached really badly, you've got all these corals spitting out their tissues and algae into the water. All of that is degrading. You get a lot of bacterial action. In really shallow areas the water starts to smell because you're getting all of this rotting tissue on the surface. You get this slick forming. The other thing though is it's not just the corals that are affected. Everything living on that reef is affected.

Sometimes you talk about wishing you could "unsee" something. When I was diving on reefs in Thailand during the major bleaching event in 2010, that is something that I would like to be able to erase and I can't. The corals were white. The fish were swimming around stunned—they didn't know where to go. The anemones were bleached white. Anemones also have zooxanthellae so they were bleaching as well. The clownfish weren't going into their anemones; they were swimming around, jumping into corals when they felt threatened rather than going into their anemones. The giant clams were bleached. They also have microscopic algae in their tissues. And everything just looked like it was in shock. The entire reef was in shock. So, when a coral reef bleaches, it's a lot more than just what happens to the individual corals, it's affecting the entire ecosystem present on that reef.

HOST: We've been talking about these rising temperatures kind of being one of the things kicking off this bleaching event. So, do bleaching events happen only then in warmer waters?

MARK EAKIN: No. Corals will bleach when temperatures get too high. That’s also the only time that we see these mass bleaching events that cover huge areas—lots of reefs in a region all at the same time bleaching because you've got this big warm water mass. You can get localized bleaching when water temperatures get too cold too fast. A little bit different reaction, some ejection of algae, a lot of times what happens in that case—like what happened in the Florida Keys in 2011—was just really cold conditions causing a lot of the coral to just die within a couple of days, much faster than what you tend to see from bleaching.

HOST: So, can a coral recover from a bleaching event or does is it tend to be fatal?

MARK EAKIN: It depends. Corals can recover and reefs can recover and we can look at both of these. An individual coral if the event is brief, if the event is not very severe, the bleaching is something that the coral can recover from by growing back its algae. There's still a small number left in the tissues—they don't get rid of all of them—so they'll get their color back.

On the reef scale, if you do have a major event and a lot of bleaching and a lot of death occurs, coral reefs can bounce back, but this gets back into some of what Jen was talking about in terms of the local stressors. A reef that is highly stressed from overfishing, from damaging fishing, especially from land-based sources of pollution, have a harder time recovering.

There was a great study that came out a couple of years ago from a reef a thousand kilometers offshore from Australia. It's very well protected because nobody goes there, there are no local threats, but it's also isolated so they can't get new corals coming in from elsewhere. So they are dependent on what happens in their reef. But what happened there, you had a lot of bleaching and mortality that occurred in the 1998 El Niño event. After the coral died, the algae started to grow, but the population of parrotfish and surgeonfish shot up, they kept all of the algae mowed down. That allowed the corals to self-recruit, so the new larval corals could have a nice place to land, could grow, could repopulate. As they repopulated, the fish, the population of those herbivores actually started to decline a bit, the algae was gone, the reef came back. If we don't stress corals in other ways, they can bounce back from these events. But if we’re stressing the reefs, it's really hard to recover.

HOST: Thank you. If we can project and look out a little bit, how does 2015 look in regards to coral bleaching?

MARK EAKIN: So, 1998 was the biggest bleaching globally that we've ever had. We lost 15-20 percent of the world's coral reefs in that year. The combination of the back-to-back El Niño and La Niña meant that a lot of areas warmed up during the El Niño, bleaching was severe all across the world, some areas don’t warm during an El Niño, but do during a La Niña and boom they got hit the next year.

2010 we had a mild El Niño, but yet we had the very same pattern of global bleaching going on—not as severe, but a lot of places were hit very badly. We're concerned about this El Niño because of the warming we're already seeing. Because the oceans are already so warm before this El Niño started that the combination of climate change with even a small El Niño is likely to cause a lot of bleaching in 2015. We've been worried about 2015 and have been concerned about what this El Niño was going to do for the last six months, what we didn't know was how bad 2014 was going to be even before we got that El Niño fully formed.

So even if we have a mild to moderate El Niño coming in—and that we'll know in the next few months—we'll see just how bad it's potentially going to be in 2015; and I'm really worried about having a lot of bleaching going on next year.

HOST: We've covered a lot on bleaching so far and I was hoping you guys could help me understand what the connection is with ocean acidification?

JENNIFER KOSS: I can start a little bit here. Ocean acidification is literally the ocean becoming more acidic. So as more CO2 is absorbed into the water column, it becomes less basic, more acidic, which puts again, another level of stress on corals. Initially slows down growth and the potential for the corals to create more of the calcareous, the hard white structure that Mark was talking about. When you get to really extreme levels, it's not just slowing growth, it's actually, in essence, eroding the reef structure.

MARK EAKIN: Coral reefs are a delicate balance between processes that build them up and processes that break them down. And that's part of the natural process of reefs. You've got a lot of things that will break down the reef. Bio-erosion—erosion by biological organisms—is a major feature of every coral reef and that makes a lot of the sand that surrounds the reefs and that we have on our beaches. So we have a very important process, but the problem again is one of balance.

As the ocean becomes more acidic there are less carbonate ions in the water. OK, so what are carbonate ions? Calcium carbonate, limestone, the material that coral reefs are made of. If you don’t have the carbonate, you don’t have the ability of the corals to make their skeletons as quickly or as readily as they usually do.

At the same time, it makes it easier for some of these eroding organisms to do their job. So, you've got more erosion happening even faster. You also can make corals weaker over time or make reefs weaker over time because of less of the cement binds that them together as they form and it makes them easier to be eroded. So you've got this major process going on where the acidification is making reefs weaker, making them grow more slowly, making them break down or dissolve more quickly.

At the same time, there's a secondary one, and that's the connection between the ocean acidification and the bleaching. That something is going on there that the additional CO2, the carbon dioxide, in the water is actually causing an increased susceptibility of corals to bleaching. So the coral will bleach at a lower temperature than it does if the CO2 weren't there.

So if you run experiments and these have been done in what are called mesocosms, basically big aquaria, and if you increase temperature, you see an increase in the amount of bleaching and mortality of corals. If you increase CO2 you see slower growth and more destruction. If you do both of them, at levels that we're almost definitely going to see around 2050 and that we're likely to see by 2100, then what you see is a reef that very quickly deteriorates into something that is not a functional reef and has very few living corals remaining.

JENNIFER KOSS: And Mark spoke eloquently about the effect of the El Niño not just on corals when he was in Thailand, but I'm sure that he could also speak to the other animals that are dependent on being able to excrete calcium carbonate shells, it's not just the corals that are being impacted by ocean acidification, there's other critters that are dependent on that same ability.

MARK EAKIN: It's effecting fish on coral reefs. The first story on fish was easy to believe. It caused them to not be able to smell where coral reefs were. Well this is not a surprise. You're affecting the water chemistry so of course it's going to affect that. They also couldn't hear the coral reefs. One of the unusual things that people just weren't expected was that larval clownfish, those anemone fish, couldn't find coral reefs in experimental test tanks because they couldn't hear what was going on any longer. So something is happening in the structure of those larvae that they're not developing properly. So not only can they not smell reefs, they can’t hear reefs.

HOST: Interesting, it's just another situation like coral bleaching where for coral bleaching it's not just the coral, it's everything around that is being impacted. It’s the same that we're seeing here. My next question was to look a little bit more about that direct impact of ocean acidification on coral reefs. But what I'm hearing from you today is there's a lot of impacts of ocean acidification on corals. There's some of these bigger things like it causes erosion, can create weaker corals, they grow more slowly, but then also that this additional carbon dioxide can cause corals to bleach at even lower temperatures than what we've seen in other environments. Is that correct?

MARK EAKIN: Exactly, that's it in a nutshell. You've got all of those plus some additional things like the larvae not being able to find the reef and things like that. So yeah, it's a major problem.

HOST: So given that there are a lot of problems out there and a lot of threats, negative impacts to our corals reefs, I'm going to ask you both this question because I hope that there's something a little more positive we can leave folks with here. What is being done to address some of these problems?

JENNIFER KOSS: So in the Coral Reef Conservation Program, we’ve chosen a policy, about seven years ago, where we narrowed our actions in terms of what we were going to do to put resources on the ground and in the water and so we narrowed down our actions to address the three main threats to coral reefs and that would be again, fishing, land-based sources of pollution, and climate change. And to the extent that we can alleviate or mitigate for local stressors, we're hoping that that will create a buffer or some sort of resilience that corals can withstand the insults that climate change are dealing them.

I have to give a talk to some second graders in a couple of weeks, I'm trying to figure out how to take all these concepts and make it something they can totally get. So the best analogy I came up with a couple of years ago is that corals in their natural state totally unimpacted by anything, we can kind of look at them like Weeble Wobbles, you can poke them and they come right back up. Like Mark said the ones off of Australia can withstand a bleaching event because everything else is OK, there's nothing else stressing. So you can poke them and they pop right back up, but they get to a certain point where they're no longer Weebles, but they're Humpty Dumpty, where you pushed them over and then he's in pieces all over the sea floor, so it's more trying to get them back to Weeble Wobble stage and not in the Humpty Dumpty stage.

MARK EAKIN: And this is really important because dealing with these local stresses is huge and it is essential because dealing with climate change, even if we were doing everything today that we could do—which we're not—it's going to take a long time to get that problem back under control. So, dealing with these local stressors makes the reefs more resilient and helps the reefs survive while we deal with climate change. Now, the good news is, there are actions that are being taken now on local levels, on national levels, on global levels to address the carbon pollution going into the atmosphere. These are things that are being addressed now and those are what we need to do to turn around this problem because as long as we're continuing to increase the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, we're going to see more warming, we're going to see more bleaching, we're going to see more acidification and it's going to take a long time to get that back under control.

HOST: I know that people who are listening to us here today and some of them may be avid divers or snorkelers and have been in these areas and they've heard everything that you've been saying. They want to feel that there's something they can do to help. Is there anything that our listeners can do to help?

JENNIFER KOSS: I think as trite as it sounds, that old bumper sticker about "Think Globally, Act Locally," is the way that anybody can go about being a good steward of their environment. So if you are a person that lives along the Mississippi River, you can think about well what kind of fertilizer should I be putting on my lawn? Well, maybe I don't need to put it on because ultimately it makes its way back to the Mississippi River and out into the Gulf, so that kind of "what can I do to reduce my impact" on the land at home right down to how can I reduce my fossil fuel consumption, my carbon footprint, thinking about ways to conserve in my day-to-day way of doing things. And then if you actually are lucky enough to live along a coastline that has coral reefs or lucky enough to go visit, to be a good steward there too, so don't walk on the reef, don't kick the reef, don't drag your diving gear, don't throw your anchor over, all of those things to not physically have a negative interaction with the reef.

MARK EAKIN: Dealing with global levels of carbon dioxide, it’s the old starfish problem. You know the story, a person's walking down the beach and there are all these starfish that have been washed up on the beach and tosses one in, tosses another one in, someone looks and says, "you're not making a dent in all these starfish." He says, "Yep, but it helped this one." So, everybody is making a difference. By changing your lightbulbs out, making sure you're going to compact fluorescent or these great new LED bulbs that are out, choosing cars that are more fuel-efficient or even electric, changing your power source. Doing these things to help us switch from a fossil fuel, high-carbon energy economy over to something that is much more based on renewables is going to be driven as much by individuals as it is by governments.

HOST: Well, thank you both for coming here today. I wanted to see if you had any final closing words that you wanted to leave folks with?

MARK EAKIN: Well, my big one is, don't get depressed over this. This is not lost. If I didn't have hopes for coral reefs, I'd go do something else like, I don't know, maybe work on icebergs in the Arctic. But really, the coral reefs have a potential, but it's really in our court. We've got to do what we can as individuals and as individuals within populations to make changes to help to keep these resources alive.

JENNIFER KOSS: I'd just echo what Mark has to say and we are working with other federal agencies as well as other countries' governments on these things and both Mark and I were lucky enough to go hear a lecture at the Australian Embassy and there was a thought that we need to really think about the ocean as one ocean for the entire planet and all think about things that we can do together. It's not just the Chesapeake Bay, the Gulf of Mexico—that we need to rethink how we think about the ocean.

HOST: Well, thank you so much Jennifer and Mark for joining us today on Diving Deeper and exploring these topics of ocean acidification and coral bleaching for our listeners. You can find more information on this topic in our show notes on oceanservice.noaa.gov/podcasts.html.

And thanks to everybody for coming back as Diving Deeper was on a break. Remember, you can follow the Ocean Service at usoceangov on Facebook, Flickr, and YouTube and noaaocean on Twitter and Pinterest to get more ocean facts, news, images, and so much more. Be sure to tune back for our next episode!

Connect with ocean experts in our podcast series that explores questions about the ocean environment. Get ready to Dive Deeper!

Subscribe to Feed | Subscribe in iTunes